Perhaps most people reading this already know what “Icons” are within the Orthodox faith. Nevertheless, “Icon” is simply the Greek word for an image or picture – any image – and therefore it’s worth exploring why some pictures are given the specific description: “Holy”.

Holiness is a characteristic of the Divine: the Father, the Son, and the Spirit, Who are Holy by nature. Everything else, which is not divine by nature, can be set apart from the fallen world by God and be rightly described as “holy” (which means “set apart”). Therefore a “scripture” means anything that is written, whereas the “Holy Scriptures” refer specifically to the writings divinely revealed to Christians: the Holy Bible (Bible coming for the Greek word for “book”). In this sense, what makes the Bible “Holy” is its content, and the source of its content.

The same is true of “Holy Images”: a picture is described as holy because of what or who the picture depicts, and the source of that depiction. In other words, an Icon is holy if:

![]()

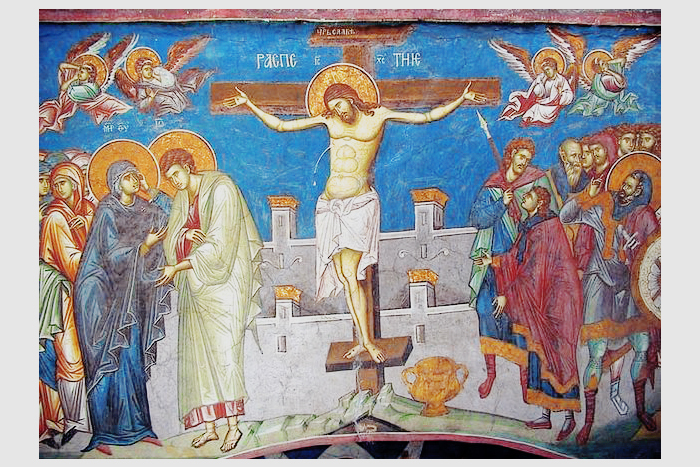

– It depicts Jesus Christ, or other Persons of the Holy Trinity, the Holy Angels, the Holy People (Saints), or other Holy things (e.g. the Cross). To continue the parallel with Holy Scripture: the Bible is “Holy” because it concerns itself with the revelation of God to man, specifically in the person of Jesus Christ. The Old Testament prefigures Him and prophesies His incarnation, whilst the New Testament describes Him fully and His life-saving death, burial and resurrection. For Christians, other books which concern themselves with other things, or strange “divine” revelations not related to Jesus Christ are not holy. The Bible is Holy because it describes holy things and holy revelation. Icons are holy where they depict holy things/persons and holy revelation: primarily in the person of Jesus Christ.

– The depiction is true. The four Gospels are not the only writings in the world that claim to describe Jesus Christ. A number of so-called gospels were rejected by the early Church. The reasons for this were all largely along the same line: the description of Jesus Christ given in these Gospels was not true. They disagreed with the Apostolic teaching on Jesus Christ, largely due to them not being written by disciples living at the time of Christ (despite their claims), and had no part within the Church, even though some had a pious intention to present Christ to the faithful. The Gospels come from the eye-witness accounts of the disciples who were there when Jesus Christ walked the earth: they are the result of divine revelation. Accounts not derived from these early testimonies do not present to us Christ but an idol: a product of the human imagination. In the same way, a Holy Icon must, ultimately, be derived from divine revelation and not from the human imagination.

There are other “conditions” sometimes given to describe what makes a picture “Holy” rather than merely beautiful or religious. Some are given below, with brief explanations as to why – I believe – they are just variations of the above two reasons for the holiness of icons.

Holy Icons must be “accurate”

When I said that a Icon must be a “true” depiction to be called holy, then I chose the word carefully. Clearly physical, outward, accuracy is a factor when describing physical, outward, events and people – whether it be in the written word or in pictures. Therefore, the Israelites sinned greatly in casting a gold statue of a calf, calling it the God Who “brought them out of Egypt” and worshiping it. They sinned primarily because they created an image of God from their own imagination: the God of the Israelites, the Creator of Heaven and Earth, has never revealed Himself in the form of a calf. Likewise, Christians do not sin in creating an image of Jesus Christ and venerating it as an image of the True God – because Jesus Christ is revealed as the True God, being of the same nature as the Father and the Holy Spirit.

Nevertheless, the physical “accuracy” of the image is of secondary importance. Drawing a parallel with the Holy Scriptures once more, we can see that the Gospel of St John concerns itself less with painstakingly recounting Jesus’ life (see John 21:25), but instead with presenting events so “that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:30-31). Likewise, an icon of Christ, an event from His life, or a picture of His Saints, are not painted to show all physical details, particularly their earthly appearance, but rather to present a true image of holiness that brings a life-saving belief. See Jesus Christ: an Icon of God for an example of how Holy Icons of Jesus Christ seek to present His true nature as God man, rather than the accurate physical appearance of the man known as Jesus, son of Joseph and Mary.

Holy Icons work miracles

Though all the Saints pray for us, and many worked miracles both before and after their repose, it is clear that not all Saints are called such because of miraculous powers. Miracles, even the miracles of Christ, are only a physical sign of divine power, rather than something which “must” be present for something to be declared holy. Many of the martyrs of the Church are called holy (Saints) despite not working any physical miracles as most people would understand them. Likewise, miracle-working icons do exist, in great numbers, but this physical manifestation of God’s grace is not needed for us to confidently call an image holy. All that is required is for the image to be of a holy thing or person, and be a true image of that holy thing or person. (See also Why does God work wonders through icons?)

Holy Icons are made in a special way

This is the belief that the piety or holiness of the iconographer effects the holiness of the image being painted. There are indeed canons, or rules, set forward – particularly in monasteries – as to how someone must approach the painting of an icon. It involves fasting, prayers, and other ascetic acts which effectively discipline the passions of the painter and allow him or her to create the icon in a prayerful attitude. Praying for the cleansing of passions and calling upon the name of God before undertaking some kind of work is clearly important, but what is its purpose specifically in iconography?

Once more turning to the example of the Holy Scriptures, it is the Orthodox belief that these writings were divinely inspired. This is sometimes shown in pictures of the Holy Evangelists, when they are depicted with an angel of God whispering into their ear as they write. This shows us that such holy scriptures are not only written accounts based on divine revelation, but also guided in their specific choice of words, by divine revelation too. But that is only true of the original manuscripts: what of the many transcriptions of the Gospels made and distributed among the early Church? Here, those given the task of transcription do not rely on being told “from Heaven” what to write: they need only painstakingly copy what is already written. Yet in doing this they must be watchful and sober, not making any mistakes, treating every word as precious, and not be tempted to edit anything based on proud self-opinion.

This then, is the purpose of the iconographer’s prayers, fasting and sobriety: to “transcribe” the holy images of the Church, already revealed and confirmed to be of divine origin. Where the iconographer is creating a “new” image (e.g. an icon of a newly-revealed Saint) then clearly the prayers also have the purpose of calling upon God, or the newly-revealed Saint, to guide their painting and ensure it is a true representation.

However, the preparation of an iconographer has little to do with his piety being transferred to the image they are painting, merely that it is through such piety that an image of a holy person can be depicted truly, without the pollution of vainglory that an “artist” might have.

In 19th century Russia, icon workshops sprouted up everywhere. These were businesses, and effectively mass-produced icons. They did this by assigning specific tasks to specific workers: one would prepare the wooden boards, another would paint the background, another would paint the figures, another the features, and so on. This is far removed from the image of a solitary monastic praying and fasting for 40 days before, with trembling hand, daring to pick up a paint brush and depict that which is holy. However, ironically, the majority of those mass-produced icons of 19th century Russia can still be called Holy. This is because by being mass-produced, the makers only cared about reproducing accurately older types of icons that were popular, and not doing anything innovative. In doing this, they preserve the subject of the Icon, and the truth of its depiction, and so the image remained “holy”.

Holy Icons need to be blessed before use

Within all Orthodox churches there are traditions regarding the blessing of new icons, whether newly painted or newly bought. The traditions vary, but usually involve bringing the icon to a priest, who then places the icon on the altar during a Divine Liturgy. Sometimes the icon spends 40 days there; sometimes special prayers are read over the icons; sometimes the prayers are accompanied by the sprinkling of holy water, sometimes they’re not.

However, if the holiness of an image derives from its prototype, then it should not be necessary for an icon of Jesus Christ, for example, to be blessed before being venerated. This is in fact the case, as I know of no priest who would argue that an icon must be blessed before veneration. The custom makes more sense if it is seen as applying to newly painted icons. In this case, the bringing of the icon to a priest, and the 40 days placed on the altar, serves as a “vetting period”, whereby the newly painted image can be observed by the clergy to see if is a true image or not; in other words whether it is an Icon of Christ or a Golden Calf.

The prayers said over the icon can be understood more as asking God that the items be blessed specifically for veneration. Thus, in the prayer for the blessing of icons we ask God: “grant that this sanctification will be to all who venerate this Icon of Saint (N), and send up their prayer unto You standing before it”. And when we pray “Bless and make holy this Icon unto Your glory, in honor and remembrance of Your Saint (N)” we are praying that the Icon be “set-apart” (holy) for the glory of God, and in remembrance of the Saint depicted. In other words, we are not praying that the Icon be made holy, for it already is if it is a true image of a holy one, but that it be made acceptable for the specific purpose of veneration. Images of Christ and the Saints that appear elsewhere (on church walls, decorating vestments etc.) are not blessed in the same manner, though they are still considered holy, because they depict someone who is holy.

Holy Icons come from an Orthodox source

It is certainly prudent for icons to be bought from an Orthodox source: a church, a monastery etc., because at least we know the money will be spent wisely (most of the time!). There is another reason, though it is not because icons made by the non-Orthodox are rendered unholy or without the grace of God. The other good reason for obtaining icons from churches or monasteries relates back to ensuring the image is a true image of a holy one, rather than a false image of the human mind (i.e. an idol). There is no such assurance when buying icons from companies who are not Orthodox, nor even Christian. Amazingly there is a company which specializes in painting and selling “Orthodox Icons”, that is closely associated with Hinduism! In such cases, being able to pick through the various images on sale, and sort out which are true images and which are false images becomes impossible and dangerous: either we fail and buy an image which is not holy, or we succeed but fall into spiritual pride in thinking we are able to decide what is “Orthodox” and what is not.

So, the testimony of the Holy Fathers, particularly those who defended the veneration of Icons, is that an image is holy because of its prototype. With the caveat that the image is a true one, an icon of Christ is holy because Jesus Christ is holy. It is not to do with it being blessed, or coming from an Orthodox iconographer who fasted for 40 days, only using certain paints and the best cypress board as his materials.

Yet I do not want to encourage anyone to declare images as Orthodox or non-Orthodox based on their own reasoning, and this “golden rule” of what makes an icon holy. God-forbid! How we sinners know an icon is holy is a different question altogether, and here we must return to the above rules, prayers and customs regarding icons. They are not superstitious rituals which confer holiness upon pieces of wood and paint. They are traditions which ensure that divinely revealed, holy, images are preserved within the Church and passed on to future generations. The rules for iconographers, the prayers of blessing, and so on are given to the faithful so that we can use these to preserve the images that are holy, and protect us from the false idols that are truly man-made. In these modern times innumerable groups claim divine revelation and even Christian revelation, presenting us with any number of contradicting images of truth and holiness. Only by trusting in the consensus of the Church regarding Holy Icons, a consensus formed by God from the works of countless Saints over the centuries, can we hope to steer ourselves through the morass of images presented to us as holy and true.