The history of liturgical singing begins in the Heavenly world, where the angelic ranks sing praise to God. Their song originates from before the creation of the world and continues in eternity. The “earthly” history of liturgical singing can be conditionally divided into several periods.

Let us look into the time during which the main system of liturgical singing known as the eight church modes was formed.

Formative Periods of Liturgical Singing

The music historian Vladimir Martynov in his research work titled History of Liturgical Singing identifies three main formative periods of church singing.

The first one begins with the Fall of Man and goes on until the prophet Moses. During that time, liturgical singing existed in its initial form. Old Testament sacrifices may well have included certain musical elements, although Scripture makes no mention of this. At the same time, music was actively used in the pagan cults followed by the peoples neighboring the Jews. The religious manifestations of God’s chosen people began to receive musical accompaniment. Moses and the sons of Israel sang songs to the Lord (Ex. 14:32), (Ex. 15:20, 21).

The second stage – from Moses to the Nativity of Christ – is a period of gradual development of the Old Testament worship and singing using musical instruments, previously serving to praise the pagan gods.

King David was a great musician and singer. He systematized the liturgical singing and created a strict system. He also organized a series of choir services in the Tabernacle, assigning trained chanters to sing in them, and limiting the worship service to the singing of psalms composed by him. “David also commanded the chiefs of the Levites to appoint their kindred as singers to raise loud sounds of joy on musical instruments, on harps and lyres and cymbals.” (1 Chronicles 15:16).

This tradition continued under King Solomon. According to V. Martynov’s research, the singers and musicians of the Jerusalem Temple constituted a separate caste within the Levine tribe. The musical gift was passed down through the family line, that is, one could only become a singer by birth.

The Incarnation of Lord Jesus Christ ushered in a third, New Testament period in which worship singing was separated from instrumental music, found its own system, and was likened to angelic singing. St. John Chrysostom in his Homily 23 on Ephesians says: “…Jesus the Son of the Father of mercies, the Son of the Very God, has brought every virtue, has brought down from Heaven all the fruits that are from thence, the songs of heaven has He brought. For the words which the Cherubim above say, these has He charged us to say also, Holy, Holy, Holy”

New Testament church singing was developed and refined over the course of several centuries, until it was finally embodied in the eight church modes. The history of the eight modes consists of two periods: the first – from the holy apostles to St. Constantine the Great – and the second – from the reign of St. Constantine to St. John of Damascus.

The Period of the Holy Apostles and Persecution

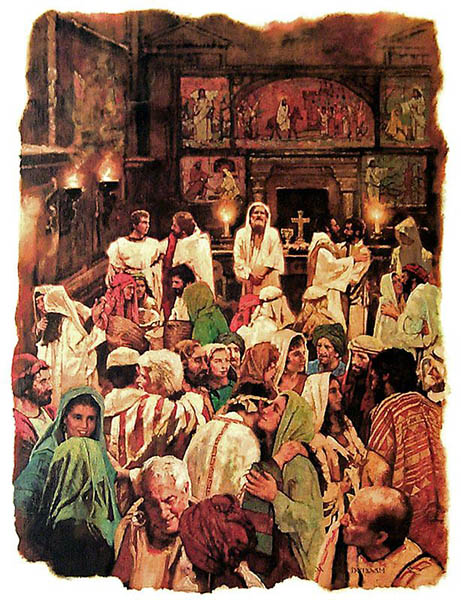

Early Christian services were still close to the Old Testament worship in the Jerusalem temple. Besides attending the Temple, the apostles and early Christians also held their own Christian meetings in their homes. These meetings were accompanied by singing. Some writers of the 1st century BC left us descriptions of such services.

Philo of Alexandria described in his book On the Contemplative Life the songs and hymns sung by the early Christians during their gatherings. Composing these chants and performing them was free and even improvisational in nature. According to Tertullian’s Apologeticum (Ch. 39), after washing their hands and lighting the lamps, everyone was invited to sing songs of praise to God, either taken from Scripture or composed by someone.

The first Christian congregations were few in number and consisted mainly of simple uneducated people. For this reason, the hymns sung by the congregation at the services were straightforward and simple in form. “After the supper they hold the sacred vigil which is conducted in the following way. They rise up all together and standing in the middle of the refectory form themselves first into two choirs, one of men and one of women, the leader and precentor chosen for each being the most honoured amongst them and also the most musical. Then they sing hymns to God composed of many measures and set to many melodies, sometimes chanting together,sometimes taking up the harmony antiphonally,hands and feet keeping time in accompaniment,and rapt with enthusiasm reproduce sometimes the lyrics of the procession, sometimes of the halt and of the wheeling and counter-wheeling of a choric dance.” (On the Contemplative Life).

Early Christian services had neither trained singers nor strict rules, except the emerging tradition for beginners to learn from the more experienced. At the same time, the following three forms of church singing, distinguished in the first centuries, are still found in worship services today:

- Hypophonic singing. The choir sings along to a more experienced singer, repeating after him either the entire melodic stanza, or its ending, or some utterance, for example, the refrain “His mercy is forever, Alleluia!” Other examples from modern liturgical practice are the refrains “For God is with us” at Great Compline on Christmas and Epiphany, or the Easter troparion “Christ is risen”.

- Antiphonal (alternate) singing. The lines of the chant are sung alternately by two choirs or by a soloist (canonarch) and a choir. Pliny the Younger (106) in a letter to Emperor Trajan wrote: “on some days Christians gather before sunrise and take turns singing hymns of praise to God.” This form was firmly established in worship thanks to St. Ignatius the Theologian, bishop of Antioch, who had a vision of angels praising the Holy Trinity in antiphonal song.

- Symphonic (consonant) singing. All participants sing the hymn in one common melody, “with one mouth and one heart”. Today’s examples of symphonic singing (depending on the local tradition) include the chants “Strengthen us, O Lord…” sung at the great vespers, “Having beheld the Resurrection of Christ” on Sunday morning, as well as “The Creed” and “Our Father” at the Liturgy.

The genres distinguished in liturgical practice included psalms, songs of praise and thanksgiving, and hymns. St. Gregory of Nyssa in his Treatise on the Inscriptions of the Psalms explains these concepts as follows: “A psalm is a melody requiring a musical instrument; a song is a melody of human voice with articulate words. A hymn is a praise given to God for the blessings bestowed upon us.”

Among the first Christian theologians working on the concept and structure of church singing in the East were St. Clement of Alexandria, St. Athanasius the Great, St. Ephraim the Syrian, St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. John Chrysostom, and others.

Although there were no outright prohibitions against the use of musical instruments in worship, they are virtually obsolete in the New Testament Church. The holy fathers considered man himself an instrument of the Holy Spirit and emphasized that proper singing is a consequence of a righteous life. “Let us become the flute, let us become the cithara of the Holy Spirit… Let us prepare ourselves for Him, as we tune musical instruments,” says St. John Chrysostom.

Thus, Christianity took a great step in the shaping and structuring of worship and church singing as early as the first centuries. Yet persecution hindered the development of its full potential.

The Period from St. Constantine the Great to St. John of Damascus

The Edict of Milan (313) by Emperor Constantine the Great made Christianity the state religion replacing the catacombs by majestic churches. Along with the outward improvements of the Church, there was also an internal refinement. The worship service was becoming more and more solemn. This affected church singing, which was taking on more and more complex forms, requiring serious preparation from the choristers.

The second period of the formation of liturgical singing was characterized by the appearance of new types of chants (e.g., troparia and stichera) and the institution of trained professional singers. Canon (15) of the Synod of Laodicea (367) states: “No others shall sing in the Church, save only the canonical singers, who go up into the ambo and sing from a book.” At the same time, according to Hieroconfessor Nicodemus (Milash), the laity were allowed to freely echo the canonical singers after they began a church canticle.

Thus, the level of liturgical singing significantly increased. Starting from that time, as V. Martynov writes, singers began to be installed in their ministry through a small blessing and a special prayer. Singers were dressed in white surplices and occupied two kliroses. The choristers constituted a distinctive entity with its own hierarchy. Along with the leading singers of the right and left choirs, there were also choristers singing unique stichera, educated mentors teaching the singers musical literacy and church composers writing new chants.

It was a great honor to be engaged in liturgical singing. Many Byzantine rulers, imitating King David, showed their skills in hymnography and songwriting. Emperor Justinian composed the hymn “Only Begotten Son”, emperors Leo the Wise and Constantine Porphyrogenitus wrote several gospel stichera and exapostilaria (songs). Many archpastors of the Church worked in this field, for example, Patriarchs Sophronius of Jerusalem, Herman of Constantinople, and Methodius I of Constantinople. Saints Basil the Great and John Chrysostom became the authors of the Liturgy.

The creation of a large number of new chants and the emergence of new melodic forms during this period led to the need to organize them into a single coherent system. In the fourth century the first system of church modes appeared. According to V. Martynov, St. Ambrose of Milan borrowed this method from the East, introducing four voices with Greek names: Protus, Deuterus, Trims, and Tetanus. In the sixth century, St. Romanos the Melodist composed kontakia and ikoi of eight tones.

In the eighth century, St. John of Damascus formulated the principle of the eight ecclesiastical modes, turning it into a perfect system. This collection of chants set to eight changeable tones was compiled into a book called the Octoechos, which is still used for divine services today. By the beginning of the tenth century, this system became common in the Eastern Church.

In the history of ecclesiastical song writing, the eight church modes became the living source of all ancient Greek, South Slavic (Bulgarian, Serbian), and Russian Orthodox chants. The Eastern Greek ecclesiastical modes used by the Orthodox Church today do not convey the exact musical forms and subtleties of the ancient Byzantine prototype. However, they contain solid musical foundations, the melodic and rhythmic properties of the Byzantine predecessor. Most importantly, they convey the same spirit, characterized by a lively, luminous religious feeling, filled with spiritual joy and hope.

St. Constantine did only set free the Church to worship, it was Theodosius the Great to make Christianity as the state religion.