The Tradition of the Church, both through divine texts and the multitude of icons depicting the feast, which encapsulate almost all of its contents and narrate about it through visual images, captures all the events mentioned in the four Gospels, that accompanied the Lord’s Entry into Jerusalem.

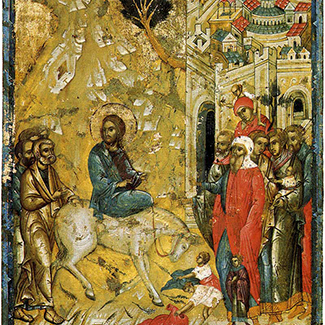

Icons of the Lord’s Entry into Jerusalem are usually distinguished by their solemnity and festivity, which is quite consistent with the character of the feast itself, which, overcoming the strict mood of Lent, foreshadows the joy of Easter. The icon gets a festive look both thanks to the image of the elegant Jerusalem, often with red or white structures, and the bright patches of garments, which its inhabitants spread on the way of the Savior’s march.

The familiar composition of the icon did not appear immediately. Although practically all icons of the Lord’s Entry into Jerusalem have a common compositional scheme, the details differ considerably. Christ is the semantic center of the icon, but not its compositional center, though in one way or another He catches the eye.

His disciples are on the left, while Jerusalem and its inhabitants are on the right. Christ sits on a donkey, and there is sometimes a young she-donkey with a colt nearby, and the apostles behind him are shown as descending from the Mount of Olives, which is a symbol of their spiritual ascent. We see people greeting Christ with branches in their hands on the right side of the composition.

The scarlet cloak on the back of a donkey reminds us of the ceremonies of imperial triumphs. Among other things that remind of triumphal processions is the ritual of throwing clothes under the hooves and the waving of palm branches in honor of the winner.

The first images related to this topic have been reliefs on Roman sarcophagi dating back to the fourth century. The simplest composition is on the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (359): the Savior rides a donkey, and a short man spreads his clothes before Him, while another man climbs up a tree.

Over time, the position of the Savior on a donkey varied from image to image. For example, He was no longer depicted riding a donkey, but sitting on the side of a donkey, with his legs hanging in the air. The position of the Savior’s head changed: in some icons He is looking not at the city, but at the apostles walking after Him. There are images where He looks straight ahead. Many Russian icons show Christ turning back to the apostles, and at the same time his body position is different: His feet are not visible. This variant of iconography became well established in Russian icon painting in the late 14th-15th centuries. It may be due to the fact that the composition was expanding as the iconography developed, and that required new solutions for the placement of the Savior’s silhouette.

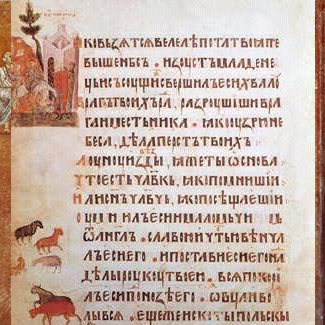

Since the 6th century the topic of the Lord’s Entry into Jerusalem appears in the book miniature, but most often in a condensed version, possibly due to lack of space.

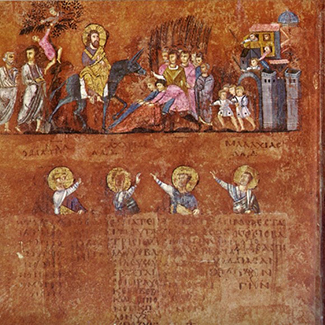

The miniature from the so-called Rossano Codex is the first to show children with branches. Jesus is riding a donkey with a scroll and a blessing hand, and two apostles are following Him, speaking to each other. Next to them is a palm tree, on which two men climb. They tear off its branches. Men and women are out to meet Christ with palm branches in their hands. There are children here, too, with branches in their hands.

Nikolai Pokrovsky, who studied the iconography of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem in detail, observed a certain discrepancy between the depiction of children and the texts of the Gospel, because, according to Matthew, children were greeting Jesus in the Temple. The so-called apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus is the only source that speaks about children cutting branches from trees and laying them on the road. It is probably under the influence of this source that children with palm branches made their way in the iconography of the feast.

However, it should also be noted that the divine service texts on the feast often mention children who meet the Lord with palm branches in their hands: “Like the children with the palms of victory, we cry out to You, O Vanquisher of death: Hosanna in the highest! Blessed is He that comes in the name of the Lord!” (Apolytikion: Tone 1).

Children are depicted on icons in white clothes as a symbol of their purity and innocence. Moreover, there are also small everyday scenes with them on some icons. Thus, they climb up a tree and cut branches, and one of the boys helps the other to get a splinter out of his leg – the palm tree is rough and you can easily drive a splinter under your skin.

The Holy Apostles were often portrayed either as a group or as just two Apostles, but the two are almost always singled out. Apostle Peter walks a little ahead, and a very young man, who can be identified as John, follows the donkey. Almost all of the images display a lively conversation among the Apostles. Presumably the Apostles are reflecting on what the Lord told them earlier.

The elaborate composition of the icon of the Lord’s Entry into Jerusalem contains the whole narrative about this event in Christ’s earthly life, emphasizing its importance and appreciating every detail. In spite of the fact that this day combines triumph and a foretaste of suffering, the light of the future resurrection, heavenly joy and a renewed life slowly but persistently flows down on us from the icons of the Feast.