This Sunday, the Church celebrates the memory of All Saints. I personally used to believe for a long time that saints weren’t unlike fairytale heroes who lived some special lives. They refused their mothers’ milk on Wednesdays and Fridays since childhood. They refused to play with their peers, walked on fire, and tamed the elements.

It took a course in ancient literature I had at the university for me to learn that hagiographies, studied by the theological discipline of hagiography, are not merely biographies or historical documents. They are a separate literary genre, characterized by its own structure and composition, as well as certain rules of description, which vary depending on the rank of the saint. Hagiographies rarely specify dates or place names, but they do contain descriptions of deeds, miracles and signs, which is what distinguishes hagiographic literature from biographies in the first place.

The first hagiographies appeared at the beginning of the Christian Church, and now they constitute almost the biggest part of the Christian literature. The first lives of saints were the stories of martyrs. Clement, Bishop of Rome, assigned seven scribes in various districts of Rome during the first persecutions of Christianity for the purpose of keeping a daily record of what happened to Christians in places of execution, as well as in prisons and courts. Despite the fact that the pagan government threatened the scribes with death, the recordings continued throughout the persecution of Christians.

Unfortunately, the ancient accounts concerning martyrs have hardly survived to this day. Generally speaking, few texts about martyrs have been preserved from the first three centuries of Christianity. On the other hand, the literary sources concerning saints of other ranks (monks et al.) are more numerous. The oldest collection of such stories written by Dorotheus of Tyre is the story about the Seventy Apostles. The other most remarkable ones are the Lives of the Venerable Monks by Patriarch Timothy of Alexandria, the collections of Palladius and the Spiritual Meadow.

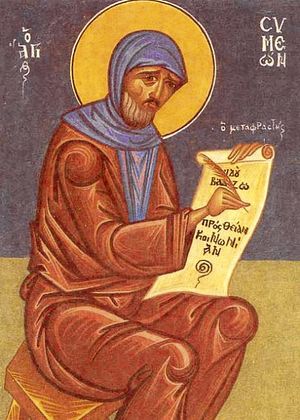

The greatest influence on the whole genre and subsequent works of hagiographic literature was the work of the Byzantine hagiographer Symeon the Metaphrast, who lived in the 10th century. His Lives of Saints also became the most common starting point for subsequent writers of this genre not only in the East, but also in the West.

St. Symeon Metaphrast (Logothete) was of noble birth and very well educated. We read his prayer in the Rule of Preparation for the Holy Communion. By commission of the Emperor, he collected several hundred hagiographies of saints. Not only did he collect them, but he also rearranged and retold them, hence his nom de guerre – Metaphrast, which is derived from the Greek word “retell”. He did a painstaking job: he corrected mistakes and inaccuracies in the texts and removed everything that could cause ridicule and mockery. Whenever Metaphrast had to deal with a single narrative about a saint, he preserved it in its original form, even if it was not reliable enough, guided by the desire to learn from the life of a little-known saint.

Ancient Russian hagiographic literature begins with the hagiographies of individual saints. They are modeled on the above-mentioned Greek writings of Symeon Metaphrast, which were intended to “praise” the saint, and the lack of information (e.g., about the first years of the saints’ lives) was filled in with generalities and lofty rhetorics. A series of the saint’s miracles is a necessary component of his hagiography, because by that time certain literary canons had already been formed. All hagiographies had a clear compositional structure – the introduction, the body, and the epilogue. The body of the text had to include the following elements: birth and upbringing of the saint, his or her feats, miracles, righteous death, and comparison with other saints.

One of the most famous Russian hagiographers and the first of them was St. Nestor the Chronicler. Another prolific hagiographer was Pachomius the Logothete: in total he wrote ten hagiographies, six legends, eighteen canons and four eulogies. Pachomius was very famous among his contemporaries and descendants, and was a model for other authors who compiled hagiographies.

The most famous hagiographic compendium was the Great Menaion Reader, compiled by Metropolitan Macarius (16th century). It was he who came up with the idea of making these compendiums the way we know them. Metropolitan Macarius did a great job of collecting information, distributing it into volumes and editing it.

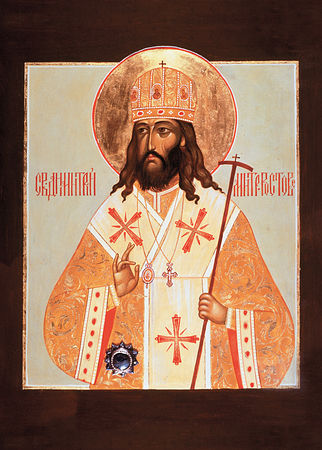

By the time when the most famous hagiography collection by St. Demetrius of Rostov (18 c.) was published, the name and works of Metropolitan Macarius had been forgotten. St. Demetrius had been working on his collection for twenty years: he revised the texts of Symeon Metaphrast and other authors, shortened the Great Menaion Reader, and added some missing hagiographies. St. Demetrius gathered the hagiographies of saints of the entire Church.

The saints’ lives in the Menaion Reader of Demetrius are arranged chronologically. There are also synaxaria for holidays, edifying remarks on the events of the saint’s life or the history of the Feast of the Holy Fathers, and some historical commentaries such as the one on the Church New Year, partly compiled by Demetrius himself. His work remains the most comprehensive collection of ancient and medieval hagiographic texts to date.

The lives of modern saints are accessible to us not only in the canonical form, but also as diaries, memoirs, historical documents, and letters, which allow us to see ordinary people who were as close to Christ as we can be, beyond the unattainable height of their spiritual life or martyrdom.