Historian Timothy Kitnis weighs the evidence on both sides

The discovery of the Holy Life-bearing Cross took occurred in 326, when the Byzantine empress Helena, the mother of St. Constantine Equal-to-the-Apostles had an excavation performed in Jerusalem at the location of Christ’s crucifixion. Some distance away from the Cross a panel was found containing an inscription purportedly made by Pontius Pilate identifying Christ as the king of Judah.

Empress Helena reportedly took the title panel — also called the Title of the Cross — with her to Rome, together with the nails, the thorns from Christ’s crown and the soil from Mount Golgotha.

Today, these relics are on display in the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem (Santa Croce in Gerusalemme) built by Emperor Constantine after his mother’s death. Scientists, however, have been in doubt about the authenticity of the title panel.

We asked Timothy Kipnis, a historian and director of the Apostle Thomas Pilgrimage Centre in Rome to brief us on the latest scholarship.

Saint Helena placed the relics that she had brought from the Holy Land in her domestic chapel, where the Church of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem was built after her death. However, these relics had to be hidden and relocated to other places, which was not unusual for the middle ages. Some relics were concealed so thoroughly that they were not discovered until many decades and centuries later. For example, the Seamless Robe of Jesus was found only when the Cathedral of Trier was rebuilt. It was not surprising, then, that the title panel was found only in 1492. It bore an inscription with the stamp of Pope Lucius II of Rome (who reigned in 1144 – 1145) confirming the veracity of the relic. Pope Alexander VI reconfirmed it in 1496.

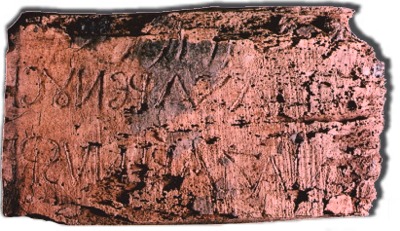

The title panel was examined for the first time in 1995 by historian Marie-Louise Rigato from the Catholic University. She photographed and weighed it. She found that the title panel was most likely made of walnut. It weighed 687 grams and measured 25 centimetres of length, 14 centimetres of width and 2.6 centimetres of thickness. Because of its age, it had been corrupted by fungi, insects and worms.

So what did the panel look like? It was a piece of wood with remnants of the inscription to which evangelist refers in his Gospel, each in his own way: “King of the Jews” (Mark 15: 26), “Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews” (John 19: 19), etc. The words “King” and “of Nazareth” are visible in Latin and Greek, but the inscription in Hebrew is almost illegible. Some scholars believe that the panel has no Hebrew text at all. But a graphical assessment proved the reverse.

In 1998, the German scholar Michael Hezemann conducted a graphical assessment of the panel and concluded that the forms of the characters in the inscription refer to the first century after Christ. He joined a group of other experts in ancient languages from several Israeli universities, and other prominent scholars who reiterated these findings in an audience with Pope John Paul II.

A subsequent radio-carbon analysis gave a different result; it dated the panel to the tenth century at the earliest. Admittedly, however, radiocarbon analysis is reliable only if the artefacts had remained in the same place, and had not been exposed to sunlight or the elements. Without these conditions (as was the case with the title panel, which had travelled a lot), the trustworthiness of the results would decrease.

These narratives demonstrate to us the wide diversity of scholarly opinion on the authenticity of the title panel. Some scholars consider it a fake, while others believe it to be the true title that Empress Helena found in Jerusalem. The latter position is upheld by the Catholic Church.

The facts may be in dispute, but the faith is standing firm. Perhaps this was the way that God had meant it to be. No object of faith – even the evangelical texts – can be proven to be authentic with one hundred per cent certainty. But is it still probable that Saint Helena found the panel next to the Life-giving Cross? By all means. Simply because all the evangelists mention it together with the Crown of Thorns and the Holy Cross in their gospels. Apostle John even talks about the bickering between the Jews and Pontius Pilate: “Pilate had a notice prepared and fastened to the cross. It read: Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews. Many of the Jews read this sign, for the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city, and the sign was written in Aramaic, Latin and Greek. The chief priests of the Jews protested to Pilate, “Do not write ‘The King of the Jews,’ but that this man claimed to be king of the Jews.” Pilate answered, “What I have written, I have written.” (John 19: 19-22).

Why was this text of the essence to the evangelists? The obvious reason is that this text represented the inadvertent acknowledgement of Christ as King. Christ had been slandered and convicted, but God’s truth still came to light: the man who died on the Cross was King. And, consequently, all of the instruments of death – the cross, the nails, the javelin and the inscription become symbols of the triumph of life over death, not the weapons of a dishonourable and gruesome execution.

Death on the cross was a punishment reserved for non-citizens of Rome – escaped slaves, or criminal offenders. In the Jewish tradition, crucifixion was not only gruesome but also demeaning. When the victim’s body was taken off the cross, the cross and all the objects pertaining to it were buried in a pit. That Saint Helena would have found the title panel next to the cross was unsurprising.

Remarkably, it was found at some distance from the Cross. By the time of Saint Helena’s coming to Jerusalem, it had been destroyed by Emperor Adrian, and she expended many efforts to establish the location of the Golgotha. As Saint Helena’s companions reported, a Pagan temple of Venus was built at Golgotha, and while it was being built, the crosses that stood there were thrown into a pit and buried. The crosses survived because of this. Yet the title panel lay separately, and it was not known to which of the crosses it belonged.

Confusion prevailed until the party saw a funeral procession — funeral rites in the East are still very moving. A widow saying her last goodbyes to her only son. The procession stopped, and the party laid three crosses on the deceased, and one of them revived him.

We mark the discovery of the Holy Cross and its exaltation as the beginning of the triumph of Christianity. Emperor Constantine promulgated the edict on legalising Christianity in 313, and the exaltation of the Cross brought Christianity into the mainstream of public life. The Roman Emperors themselves had bowed to the Cross.

It is also noteworthy that the Exaltation of the Cross is celebrated on the fortieth day of the Holy Transfiguration when the Lord revealed to His disciples His Divine nature.

So what is the meaning of our veneration of the Holy Cross? We do not venerate the wood, but the Divine Life-bearing power. In this sense, any of our remaining doubts about the authenticity of the title panel are irrelevant. When we come to the Church of the Holy Cross, we bow to the relics kept there – the title panel, the cross, the thorns, and also the finger of Apostle Thomas that he put between the ribs of the Saviour. We venerate His Divine Power, His triumph, and the light of Tabor seen by His apostles.

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://foma.ru/tablichka-s-kresta-gospodnya-v-rime-svyatyinya-ili-poddelka.html