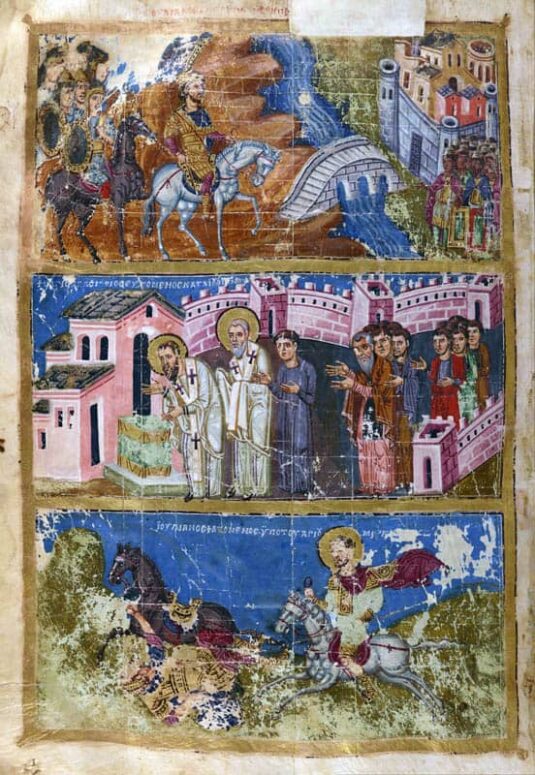

2 November, Commemoration of Saint Artemius of Antioch

Artemius, a distinguished military commander, reached the peak of his military career during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine the Great and his son and successor Constantius. For his superior service, he earned multiple awards and eventually became the Prefect of Egypt. He converted to Christ and became a devout and passionate believer, sparing no effort to promote and spread the faith across Egypt. Yet in his life, and likewise in the lives of thousands of his contemporaries and fellow believers, there was one decisive moment – the ascent to power of Flavius Claudius Julian, better known as Julian the Apostate. How did this philosopher who went to school with Basil the Great become a persecutor of Christians?

Growing up in isolation

He was a nephew of Emperor Constantine the Great. Orphaned at six years of age, he was raised by Mardonius, a eunuch who planted in him a taste for the Hellenistic tradition. Neo-platonic philosophers were his teachers. Long years of isolation under the Christian emperors caused him great pain, to which some historians attribute his dislike for Christianity.

Nevertheless, he engaged in theology as an adolescent and even served as a reader at a church in Cappadocia. However, at eighteen, he became attracted to mystical teachings. Ultimately, he became a secret convert to Paganism by partaking in the Eleusian mysteries.

Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian, who studied with Julian the Apostate at the University of Athens, remembered him as a loner and hermit. Ostensibly, his behaviour had a plausible reason. In 351, Emperor Constantius appointed his brother Gallus the Caesar of Antioch. He ruled by fear and terror and raised so much discontent that Constantius had him recalled and executed after two years. Understandably, Julian may have had good reasons to be reticent under these circumstances.

This time, the storm left him unaffected. Emperor Constantius summoned him from Athens, married him to his Christian sister and sent him to the remote provinces of Gallia and Brittany as Caesar. Centuries later, this territory would become the centre of France. But at his time, it was at the periphery of the Empire, with few philosophers or intellectuals to spend time with in learned debates. Locked up in a military garrison, he spent all his time fighting back the rebellious Germanic tribes.

Mindful of the fate of his brother, Julian enticed his soldiers to proclaim him the sole ruler of the land when the emperor summoned him to the capital. Constantius was not happy. A civil war was brewing. Unexpectedly, Constantius died, and Julian inherited his throne. From the first weeks of his reign, he was hard at work on his pet project – restoring Paganism in Rome.

Covert persecution of Christians

A philosopher and intellectual, Julian knew well that the return to Paganism in its past form was impossible in an empire without a single active Pagan temple even in its capital. His real aim was to rebuild a Pagan hierarchy in the image and likeness of the hierarchy of the Christian Church.

He began by proclaiming a policy of religious tolerance. He returned from exile condemned Christian heretics, launched public religious disputes and permitted the rebuilding of confiscated Pagan temples converted by Christians into churches. In the words of Saint Jerome, his actions amounted to soft persecution that encouraged idolatry but did not enforce it. Unlike his predecessors from Nero to Diocletian, Julian relied on indoctrination, not terror. He did not torture or execute Christians. He used sarcasm and irony instead, denying Christians the support of the state.

However, he also used some violence, as evidenced by the presence in the Menaion of the saints martyred during his reign. Julian’s reforms created a dangerous situation. To comply with his orders, Christians were obliged to destroy their churches and sometimes to rebuild Pagan temples at their cost. Sometimes, Pagans claimed from the Christians the properties that had always belonged to the Christian Church.

Anti-Christian indoctrination

Julian was generally averse to creating martyrs. Their martyrdom only strengthened Christians in the faith, which he believed was counter-productive. He preferred to use a more laissez-faire approach. In Alexandria, for example, a crowd of Pagans tore to pieces the Arian bishop Georgias at the news about the death of Emperor Constantius. Julian rebuked them diplomatically for taking the law into their hands.

The Emperor travelled extensively, visiting towns and cities where Christians were in the majority. He preached enlightened Paganism. In Cappadocia, he complained that its people had become so ‘Christianised’ that they forgot how to sacrifice to idols. He arranged the public worshipping of idols and participated in them with the zeal of a neophyte, giving cause for rumours and ridicule.

Frustrated and unpopular

Increasingly, Julian was becoming frustrated. Most Pagans – even the Pagan Magi – did not share his vision of Paganism. In their worship of the idols, the people remained lukewarm and lacked enthusiasm; sometimes, only old women came to the acts of public idolatry attended by the Pagan emperor.

Intellectuals found him too superstitious and ordinary people too sophisticated. The Pagan Magi found his new rules and restrictions too uncomfortable: they could not bring themselves to engage in generous almsgiving or abstain from attending impious gatherings, going to taverns, reading frivolous literature or engaging in untoward activities.

Increasingly, he felt disheartened and embittered. Finally, he heeded the advice of his top Magi, the Augurs, to show the people the power of the old gods. To do so, he mounted an attack on Persia, in defiance of all common sense.

He had the habit of conferring with the Augurs in all important matters. In Antioch, where he was delayed for several months en route to Persia, this habit had some tragic consequences.

Bad omens

While in Antioch, misfortunes dogged him at every corner. Even the decision to stay there for the winter was a mistake. Julian was highly unpopular and unwelcome in this Eastern City.

In his time, Antioch was one of the centres of Hellenism. Its faithful took pride in the fact that it was there that the believers in Christ first got the name Christians. Christianity largely coexisted with Paganism, but tensions between the two communities occurred from time to time.

In the suburb of Antioch Daphna, there stood the temple of Apollo with a famous Oracle. Daphna even hosted Olympic games in the Greek tradition. In 351, Julian’s elder brother Gallus transferred to Daphna the relics of the Holy Martyr Babylas. The Christian and Pagan sanctuaries located close by instigated tensions.

In Antioch, Julian predictably wished to hear the prophecies of the Daphna oracle. But the closeness of the Christian martyr’s relics interfered with his session, so he ordered them to be moved to another place. A large crowd of Christians gathered to fulfil his order. They put the reliquary on a hearth and drove it away singing Church hymns.

A short while later, Apollo’s temple caught fire and burned down. Immediately, Julian ordered the closure of the city’s Christian cathedral.

The demise of the apostate

For the doomed Emperor, the fire was yet another foreboding of his peril. Annoyed, he ordered a thorough investigation. He was confident that the arsonist was a Christian.

Sensing the attitude of the Emperor, Pagans ransacked and desecrated the cathedral. Pagans in other cities followed suit. Christians responded by destroying the Pagan idols.

The emperor ordered the execution of the Christian Prefect Artemius for allowing the destruction of the Pagan temples to proceed. Christians collected and buried his remains, and later transferred them to Constantinople. A piece of his relics was also brought to the Kiev Caves monastery.

Julian the Apostate perished during his retreat from Mesopotamia.

Sozomen, author of the Christian History wrote about his death, “While preparing for the was in Persia, he promised harsh times for the Christian churches. He was repelled, and he knew where the defeat had come from. They say that when he received his deadly wound, he collected the blood that trickled down from it into the palm of his hand and threw it at Christ Who appeared to him in a vision.”

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://foma.ru/kak-razvalilsja-proekt-juliana-otstupnika-po-vozrozhdeniju-jazychestva.html