In our age, it is hard to imagine how anyone could accept monastic tonsure against their will. At church, tonsure is a holy sacrament, performed on a monastic. In it, the new monastic takes vows and has her hair cut, as a sign of her belonging to the Holy Church. A monastic dies for the world, takes a new name and starts a new life of service and dedication to God in a monastery or a hermitage.

Yet many centuries ago, some monasteries became places of exile for members of the laity, clergy or the royalty who had committed a misdeed or had fallen into disfavour with the supreme rulers. Although monasticism was not their free choice, many saw in their involuntary tonsure the will of God and spent the remainder of their lives ascending to sanctity.

Byzantine practices

In Byzantine, exile and incarceration in a monastery was not extraordinary, and was practised from the beginning of monasticism. In the East, monasticism appeared two centuries earlier than elsewhere in the world. Yet, in those early times, Saint Anthony of Egypt wrote in his rules of monastic living, “Rebuke (and chastise) your (spiritual) children unrelentingly; for you will be responsible if they the Terrible Judgement of God condemns them.”

Perhaps these ideas of the founder of monasticism – interpreted by the leaders of society in a manner they found convenient – gave rise to the unusual practice of incarceration at a monastery to reform an offender. For members of the clergy and monastics, it became the norm as early as the fifth century.

From the reign of Emperor Justinian, involuntary tonsure became a legal penalty for the laity. For example, Justinian’s Novel 141 stipulated that a wife who defiled herself by committing adultery could be sent to a monastery to repent her sins. She would remain there for the rest of her life if her husband did not take her back within two years of her exile. The ninth-century collection of laws “Basilika” mandated that spouses who dissolved their marriage without a valid reason both be exiled to monasteries indefinitely. In addition, they gave up all of their estate, part to the monastery and the rest to their kin.

Incarceration at monasteries of disfavoured royals and members of the royal court became the practice in Byzantine in the seventh century. In addition to an act of repentance, the guilty persons also took involuntary tonsure. One example of a member of the royalty who took involuntary tonsure was Saint Theodora, the wife of Emperor Theophyl of Byzantine, a prominent iconoclast. After her husband’s death, Theodora took the affairs of the kingdom into her hands; eventually, however, she encountered opposition from her brother. He isolated her from power and forced her to take monastic tonsure along with her daughters. In monasticism, Theodora took the path of spiritual advancement and departed peacefully to God in the grace of His spirit.

In Byzantine, exile to a monastery was also seen as a humane alternative to the death penalty and other forms of harsh secular punishments. In the tenth century, the Byzantine emperor Constantine promulgated an edict recommending to all uncaught murderers to take monastic tonsure and earn themselves forgiveness from God in monastic labours and prayer. Individuals who took the offer were exempt from secular penalties for their deeds.

Medieval Russia

After Christianisation, Russia gradually adopted the Byzantine practice of ‘humane punishments’ in the form of exile to a monastery. Initially, such punishments applied only to women who married a second time during the life of their first husband or defiled themselves in other behaviours that constituted adultery in marriage. The first mention of a politically motivated forced tonsure dates back to the reign of the Kievan Duke Igor Olgerdovich. In 1146, he was deposed and sent to a monastery where he took tonsure. As a monk, he died at the hands of an assassin and was canonised by the Church as a saint. The wonderworking Igorevskaya icon of the Mother of God was named in his honour.

Medieval Russian history has multiple examples of royals exiled to monasteries against their will. Some of them accepted their involuntary tonsure as the will of God and lived pious and ascetic lives fully dedicating themselves to His service. Let us look at some examples.

Perhaps the most prominent of all was the example of Grand Duchess Solomina Saburova. In 1505, this pious young woman was chosen among hundreds of others to become the wife of the Russian Tsar Basil III. The spouses lived in peace and harmony for many years. However, after twenty years of marriage, Solomonia could not bear him a son, and the Russian Tsar resolved to try his luck with another woman. In his time, however, divorce was not an option. Although the Boyar Duma supported the Tsar’s decision to dissolve the marriage, Metropolitan Barlaam, Maxim the Greek and other clergy Were firmly opposed. As a result of this standoff, Barlaam became the first metropolitan in Russian history to be defrocked. Solomonia was forced to take tonsure with the name Sofia and sent away to the Monastery of the Protection of the Mother of God in Suzdal. Eventually, that monastery became the place of exile for many other hapless spouses of Russian monarchs.

The German Baron Sigusmundus Herberstein left the following account of Solomonia’s involuntary tonsure in his work “Notes from Muscovy” “Saddened by her wife’s infertility, he committed her to a monastery in the Dukedom of Suzdal in [1526], the year our arrival in Moscow. She cried and objected vehemently as the metropolitan was cutting her hair, and when he handed her the koukolion to cover her head, she did not allow him to put it on her. She threw it on the ground and trampled it with her feet. Enraged at her rebelliousness, the Tsar’s top counsellor John Shigona, reprimanded her harshly and even struck her with a lash. “How dare you oppose the will of the Tsar and disobey his direct orders?” he explained. When Solomonia asked why he had struck her, he answered, “On the orders of the Tsar.” Distraught, she announced to everyone present that she was putting on her monastic robe against her will and asked for God’s punishment for those guilty of this injustice.”

All the Eastern Church patriarchs condemned the Tsar’s actions. According to tradition, the Patriarch of Jerusalem prophesied that the boy who would grow up in the new marriage would strike the whole world with his cruelty. The prophecy came true. Tsar Basil III married Elena Glinskaya, and four years later they had a baby boy, the would-be Tsar Ivan the Terrible.

It took Nun Sophia many years to come to terms with her new situation, but finally, she found her peace in prayer and dedicated the rest of her life to the service of God. She departed peacefully in 1542. Her informal veneration as a saint spread across Russia, and many of her contemporaries joined in her commemoration. The faithful who visited her grave and the resident of Suzdal reported multiple miracles that happened through the prayers of Saint Sophia.

Many Russian monarchs followed the example of Basil III in getting rid of their spouses when they saw fit, and his son John the Terrible was the first among them.

Tsarina Anna Koltovsksys was his fourth wife. After living together for about six months, the Tsar had her sent away to the monastery in Suzdal, where she was made to take tonsure with the name Daria. In 1604, the former Tsarina moved to the Monastery of the Entrance of the Holy Theotokos to the Temple in Tikhvin, where she became abbess. After her peaceful departure, she was revered locally.

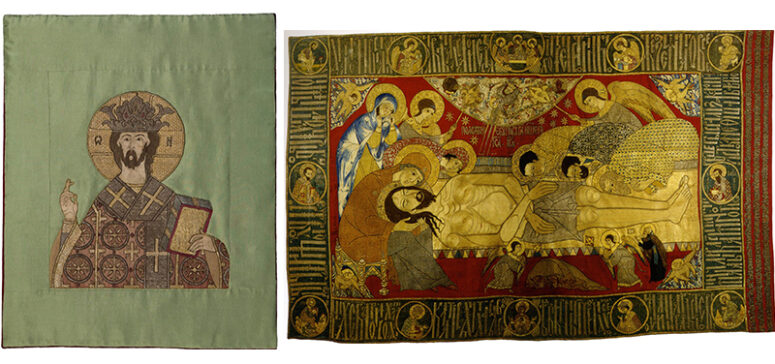

Princess Euphrosyne Staritskaya was married to Prince Andrey Staritsky. After her husband’s death, some of the Boyars supported her son Vladimir as an alternative to Tsarevich Dmitry as successor to the throne. Infighting followed, and in 1563 supporters of Ivan the Terrible reported Euphrosyne to the Russian Tsar. Suspicious that she was plotting against him, the Tsar exiled her to the monastery of the Resurrection of the Lord at Gorista, which she had established. She took tonsure with the name Evdokia. She was allowed to bring with her handmaids and confidantes and visit the neighbouring villages for prayer and on other business. To that monastery, she also transferred her goldwork workshop. Twelve pieces of artwork from that workshop have survived to this day.

Soon after the assassination of her son Vladimir, Euphrosyne accepted martyrdom, too. On orders from the Tsar, her assassins drowned her in the river along with the nuns who accompanied her. Also martyred with Euphrosyne was the Tsar’s daughter in law Juliania Paletskaya (Alexandra in monasticism). The bodies of Evdokia and Alexandra were recovered from the river and buried with honour at the Goritsa Monastery, and the duchesses were glorified as local saints of the Vologda Area.

God gives every man and woman their free will. Sometimes, power-hungry politicians trampled on the free will of their subjects trying to ‘bring change’ in them by force or keep them out of their sight. Yet even in those circumstances, the Lord left them the choice – to bide their time or to ascend to sanctity.