The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31) is often treated quite differently than Christ’s other parables. None of the others have the history of being taken quite so literally. This parable is often mined for details and cited authoritatively in regard to concepts of the afterlife or at least of the intermediate state of souls between the time of a person’s death and the general resurrection at the time of Christ’s glorious appearing. In some cases, this goes so far as an argument that this story may not even be a parable as it is not identified as one in the text. Arguing against this last assertion is the fact that the Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37) is likewise not identified as a parable and in Greek begins almost identically. The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, however, is very clearly a parable as it represents one of a whole genre of similar stories in the ancient world that utilizes the same motifs and themes.

The search for preceding parallels to elements of the text of the Scriptures, a part of what is called source criticism, is often misused. It is misused based on a false presupposition that unless every element of the Biblical text is utterly unique in its cultural milieu then it cannot have any divine element. If the Scriptures are themselves firmly grounded in the times, places, and cultures of their composition then they cannot function in an authoritative way. This presupposition, however, is obviously false. At a base level, the Scriptures were composed in languages, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, which already existed using words that had previously been coined. From the fact that the Scriptures did not have to invent their own language flows naturally the fact that they do not need to invent their own completely new set of themes, motifs, images, and narratives. The Scriptures do not create a new world. Rather, the Scriptures correct the human understanding of the created world in which all humans live. They are therefore communicating about the same objects as non-Scriptural texts and doing so in a way that was perfectly intelligible to their original hearers.

There are two primary motifs found in the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus. The first is the story of a reversal of fortune for a rich man and a poor man after their deaths. The second is the idea of a person potentially returning from the grave to issue a warning or revelation to the living. Reading and understanding the parallel ancient stories which utilize these two motifs is important to understand the major themes of the parable. Rather than rendering St. Luke’s text irrelevant because similar stories exist, Christ’s parable utilizes the themes of the parallel stories but also transforms them. This transformation is found in the places in which the parable diverges and differs from the usual paradigm of these motifs.

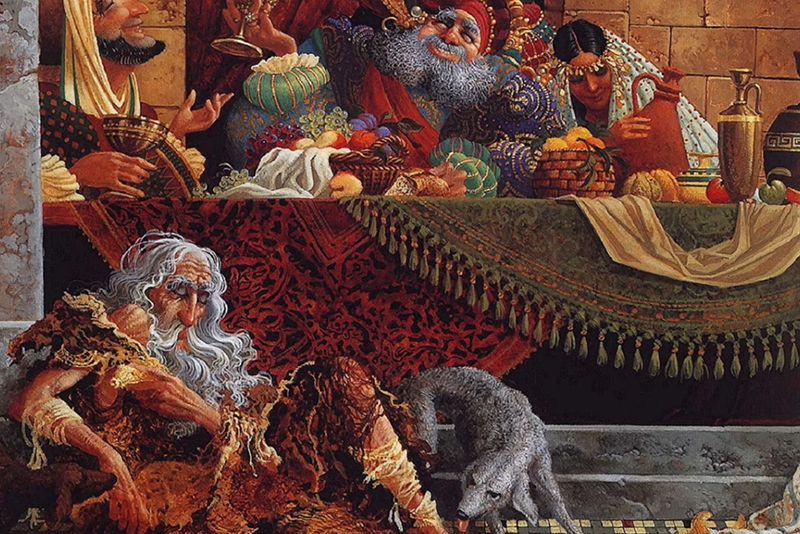

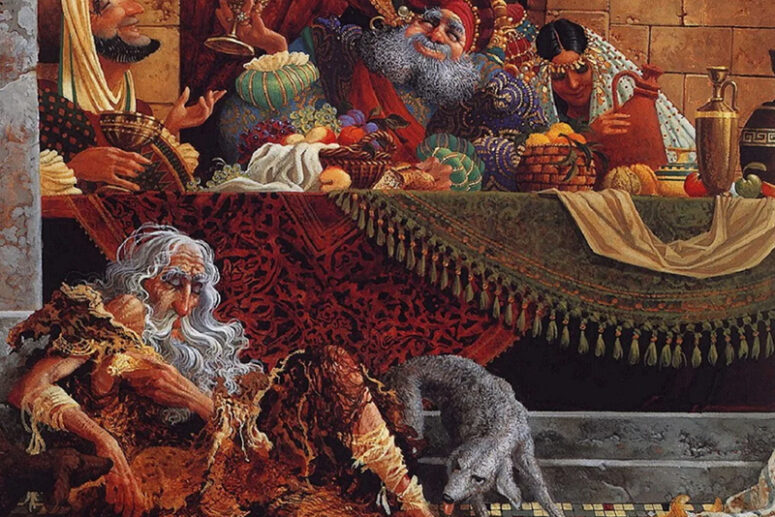

There are a number of stories from the ancient world which involve the deaths of a wealthy man and a poor man, followed by a revelation of their opposing fates in the afterlife. The prime example, which was current in the first century AD, is a portion of the story of Setme and Si-Osiris of Egyptian origin. The relevant episode is only a small portion of the overall story, but in it, Setme and his son Si-Osiris observe two burials. The first is that of a wealthy man who is given an opulent funeral complete with paid mourners. The second is that of a poor beggar who is rather unceremoniously thrown into a grave. Setme indicates that he hopes his funeral will be like that of the rich man. Si-Osiris tells him he should not be too hasty and takes him on a journey to the sacred realm of Osiris, Amente. Touring the halls of Amente, Setme sees the wicked, including the wealthy man, being tortured for their wickedness. The beggar, on the other hand, because he was righteous, is seated and feasting with Osiris. This includes both the element of the reversal of fortunes of a wealthy and a poor man and the idea of a visit to the underworld which reveals their fate to the living as a warning. In the 2nd century, Lucian in two dialogues told a similar tale in the second century AD of a journey to Hades with a rich man, a philosopher, and a poor man.

Stories which include the second motif, of a visitor to the underworld returning to issue a warning, are commonplace in the ancient world. The vast majority of apocalyptic journeys in Second Temple literature include such a visit to the underworld and to Paradise. Visits to Hades in visions and dreams are a commonplace in Greek and Roman literature, including Plato’s story of Er the Pamphylian in the Republic and tales related by Plutarch, Pliny, and others. St. Augustine relates Christianized versions of these Roman stories in his City of God. Unlike these other stories, in Christ’s parable the rich man’s request, rational considering the parallels, is declined. The explicit basis for this within the parable is that everything necessary to avoid the fate of the rich man is already revealed within the Torah and Prophets (Luke 16:29-31). There is also, however, clearly an allusion made to the theme of Christ being the one who has descended from heaven and will rise from the dead bringing revelation (see John 3:13; Eph 4:8-12).

Aside from the rejection of a messenger being sent from Hades, the parable deviates from other similar stories in a significant way. The focus of the stories regarding the fates of the rich man and the poor man is on the punishment of the sins of the former. This is often, as in the story of Setme and Si-Osiris, described in gruesome detail. Particular elements of wickedness receive related punishments in pagan sources out of a sense of irony. The parable is clear that the rich man is in torment (Luke 16:23), but does not describe particular punishments which are somehow suited to his particular wickedness. In fact, the wickedness of the rich man is never actually described or even posited. All that we are told about him is that he is wealthy and well-fed. Likewise, there is no expression given in the parable to any particular virtue, piety, or good deeds of Lazarus for which he is being rewarded. Rather, the parable explicitly explains their fate by pointing out that in their earthly lives, the rich man received his good things and Lazarus bad (v. 25). The parable itself offers no reason for the condemnation of the rich man to torment other than his wealth and no other reason for Lazarus’ comfort other than his poverty.

This is in keeping with a general tendency on the part of St. Luke as evidenced by a comparison of his beatitudes and woes with the beatitudes of St. Matthew’s Gospel (cf. Luke 6:20,24; Matt 5:3). St. Luke’s wording is key. In his woes, he says that the rich have already received “their comfort.” Abraham says to the rich man that in his life he had received “his good things.” Likewise, the parallel structure indicates that Abraham is not only indicating that Lazarus had received bad things in life but “his bad things.” These possessives, while easily glossed over, are critical to understanding the thrust of the parable and how it relates wealth to sin.

There is a later variation on the story of Setme and Si-Osiris found in two tractates of the Talmud (Sanh. 23c; Hag. 77d). This story reflects details of the Egyptian story which reveal it as the source. In its changes, however, from that source, it reveals, as does much of Rabbinic literature, clear Christian influences. In this variation, the rich man is a wealthy tax-collector named Bar-Mayan while the poor man is a poverty-stricken Torah scholar who lives in Ashkelon. Not only does this seemingly incorporate a reversal of the Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican, but it also reverses the unknown name of the rich man and the named poor man from the Rich Man and Lazarus. It is likely also not a coincidence that there is a woman named Mary being tortured in the underworld in this version. The key element for purposes of understanding the latter parable, however, is the justification given for the sufferings of the rich man and the blessings of the poor man. The opulent burial of the rich man was the reward for the one good deed he did in his life, while his sufferings were the punishment for his many wicked deeds. Likewise, the poor man had committed one sin in his life and as punishment for it he had died ignominiously. The reward for his many good deeds awaited him in the afterlife.

Blessings, then, including material blessings are seen as rewards. Sufferings, likewise, are seen as punishments. Reward and punishment language simply indicate the consequences of actions that are mediated through a third party, in this case, Christ who judges. The rich man, as evidenced by his sumptuous feasting, lived a life that sought to maximize both his material blessings and pleasures of this world. Lazarus, by contrast, received poverty and hunger and endured them as punishment for his sins. This receiving of life’s sufferings as chastening for sins is at the core of the Christian concept of repentance. The rich man, by contrast, evaded and avoided suffering by all necessary means, therefore leaving his sins unrepented. He had already received more than his due of comfort, Lazarus had not and so he received it in Paradise. Lazarus had already received his due of bad things, the rich man had left them for Hades.

This connection between reward and punishment in this life over against the next is found throughout the Synoptic Gospels and the rest of the New Testament. Those who have enjoyed the pleasures and wealth of this world have “received their reward already” (Matt 6:1-24). Rather than accumulating treasures on earth, we are commanded to store up treasures in heaven (v. 19-20). Those who refuse to repent in this life are “storing up wrath” for themselves for the Day of Judgment (Rom 2:5). Moses chose to suffer with the Israelites because he “considered the reproach of Christ greater wealth than the treasures of Egypt because he was seeking the reward” (Heb 11:26). Christ teaches that those who suffer for his sake should rejoice for their reward is great in heaven (Matt 5:12; Luke 6:23). He promises a reward for acts as simple as the giving of a cup of cold water (Matt 10:42; Mark 9:41). He promises a great reward in the kingdom to those who love their enemies, do good, and lend without hope of repayment (Luke 6:35). The penitent thief expresses his repentance by telling his fellow that they are receiving the due reward of their evil deeds in their crucifixion (Luke 23:41). Eternal life in the world to come is repeatedly described as a reward (1 Cor 3:14; Col 3:24; Heb 10:35; 11:6; 2 John 1:8).

This means that for the Christian who has been richly blessed in this life, a dilemma is created. Material wealth is the most obvious form of these blessings and often the means by which other blessings, pleasures, and good things of this world are acquired. Asceticism is, therefore, the marrow of the Christian way of life and the core of repentance. Asceticism takes a variety of forms, but for the early fathers, central to these was the giving of alms. This is immediately apparent when surveying the early interpretation of 1 Peter 4:8. St. Peter states that due to the nearness of the final judgment, his hearers must have constant love because “love covers a multitude of sins.” The “covering of a multitude of sins” in this text was directly connected to the concept of atonement, literally the ‘covering of sins’ in Aramaic. The “love” here directed was understood to explicitly refer to the giving of mercy to the poor. This interpretation is found in 2 Clement, the Didascalia Apostolorum, St. Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, and Origen as well as a number of later fathers. St. Clement finds it in 1 Clement as well. The voluntary divestiture of blessings in this world is seen to atone for sin both by postponing those blessings for the world to come and by accepting the resulting hardship.

That hardship forms a basic building block of repentance when it is received as repentance for sin. St. Ignatius of Antioch criticizes the docetic teachers of Smyrna because “they have no concern for love, none for the widow, none for the orphan, none for the oppressed, none for the one who is in chains or the one released, none for the one who is hungry or the one who thirsts” (6.2). He argues that it would be better for them if they were to love in this way, as then they would partake of the resurrection (7.1). 2 Clement tells us that, “He says, ‘Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord” will be saved but the one who does righteousness’…we should be self-controlled, practitioners of mercy, benevolent. And we should suffer together with one another and not love money” (4:2-3). St. Polycarp, in his Epistle to the Philippians, cites Tobit 4:10 and 12:9 as an instruction to the Church, “alms-giving delivers a man from death” (7.2). The Didache instructs, “If you have something through the work of your hands, then give a redemption for your sins” (4.6). These themes find their denouement in St. Cyprian of Carthage’s treatise on the subject, On Works of Mercy (De Opere et Eleemosynis).

A story from the Acts of Thomas provides a suitable closing illustration. The Acts describe Thomas’ journey to India to proclaim the gospel. Due to its non-canonical status, it has been much neglected, though the third-century text has been preserved by the Church in both the original Syriac and Greek. It was, until very recently, considered to be of no historical value even with reference to the history of the Church in India. Recently, however, the unearthing of a cache of coins bearing the name of the Indian king central to the story, Guandaphur, has yielded reconsideration as to the veracity of at least some of the traditions contained therein. The Acts present St. Thomas as a craftsman and builder by trade who comes to India as a slave and is given service by King Guandaphur to build for him a new palace. It is eventually revealed that in actuality, St. Thomas has built nothing but has been distributing all of the money given to him by the king to the poor and proclaiming the gospel. When he discovers this, the king has the apostle thrown into prison to await execution. St. Thomas offers as his only defense that he has, indeed, built the palace for the king who does not need the money he was given in this world because he will receive a king’s reward. That night, the king’s brother dies. He is taken to the heavens and there sees a magnificent palace. When he inquires about it, he is told that that is the palace built for his brother the king by St. Thomas through his acts of mercy. The king’s brother asks to return to this world to bring the news to his brother and the request is granted. When Guandaphur heard his brother’s report after being raised from the dead, he immediately freed St. Thomas and embraced Christianity, becoming the sponsor of St. Thomas’ mission in India.